Doss’ strong faith, deep-rooted principles and his refusal to compromise with his conscience made him a man of integrity – one whose contributions continue to make a difference.

By Natalia Grobler.

Following the war, Doss spent more than five years in hospital recovering from his injuries sustained during battle. Doctors also discovered that he had tuberculosis. One of his lungs was removed, as were five ribs. His disabilities prevented him from seeking employment and he spent his post-war years living on a modest pension.

Doss was honourably discharged from the army in 1946. Doss and his wife Dorothy, who he had married in 1942, had one son, Desmond Jr. They moved to Rising Fawn in Georgia in the 1950s, where they purchased five acres, farmed and built their home.

Doss continued to devote himself to God, working with young people in church-sponsored programmes including a military training camp in Michigan for Seventh-day Adventist youth. Doss was featured on the This Is Your Life television show in 1959, after which he received many public speaking engagements.

Dorothy died in 1991 and Doss remarried Frances Duman who wrote Desmond Doss: In God’s Care in 1998. It was later reprinted as Desmond Doss, Conscientious Objector in 2005. Doss died at the age of 87 on 23 March, 2006.

During his life Doss faced unscrupulous and relentless adversity that must at times have been crippling. The disappointment could easily have led to despair and bitterness but instead he chose to persevere. Doss did what he knew to be right, breaking down stereotypes, showing incredible commitment and devotion to the very soldiers who had once mocked and rejected him. Time and time again, he demonstrated fearless bravery and selfless compassion for the suffering of the men he served.

Doss’ strong faith, deep-rooted principles and his refusal to compromise with his conscience made him a man of integrity. God honoured Doss using him in ways far greater than he could ever have dreamt possible — in ways that are still playing out today nearly 75 years later.

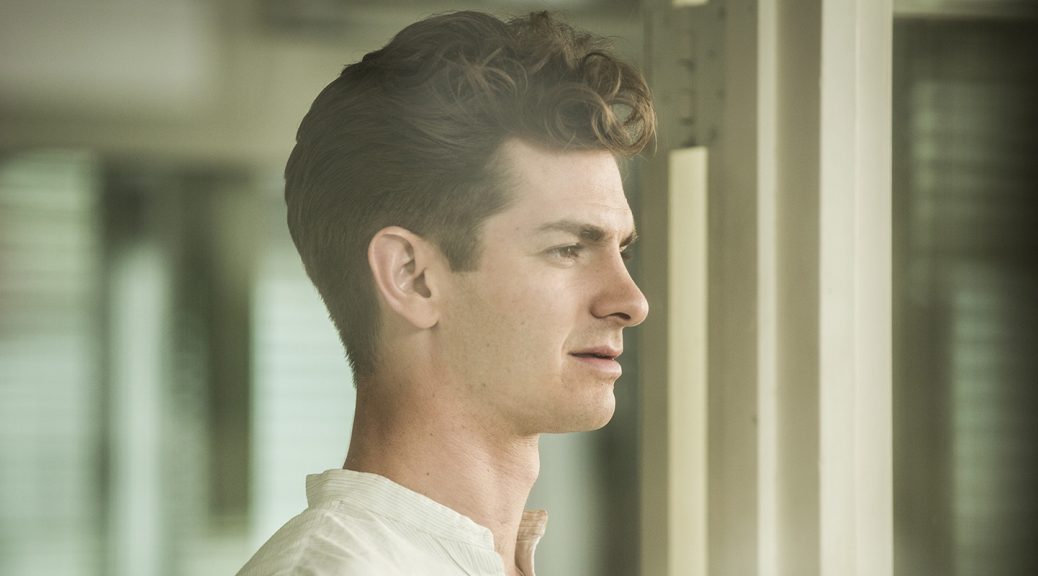

Image courtesy of Desmond Doss Council.